Group living - herbivores

Many herbivorous dinosaurs lived together, walked together (and stepped on each other's toes and tails), and then died together. Evidence of this can be seen in communal nesting sites, bone injuries, tracks, and bone beds. What does this mean for our understanding of dinosaur life?

Our research tells us that group life is complex. Animals need to recognize each other, compete for social status, and mate. To succeed in these areas, one needs strength or size, displays of features such as antlers or deer antlers, or certain behaviors. If we can detect any of these in dinosaur fossils, it indicates that they faced similar concerns—and we need to re-examine their spikes, antlers, and elaborate headdresses.

The advantages of grazing can be seen in modern animals. Larger numbers reduce the risk of predator attacks and help raise offspring. A bed of Centrosaurus apertus bones in Alberta, Canada , which was drowned about 75 million years ago, contains the remains of more than 300 individuals of different age groups, providing strong evidence of their gregarious lifestyle.

Cohabitation - Carnivores

Our understanding of solitary predators is changing. Recent fossil discoveries suggest that some animals lived in cooperative groups, raised offspring, and were likely highly social. This helps to dismantle the stereotype of "built purely for killing," but it also raises a whole new set of questions. Were the groups family-based, male- or female-dominated, or something else entirely? Did they hunt in packs or compete for social status and mates? While fossils are fascinating, they don't provide definitive answers. Our only insights come from extant predators—who simply tell us that theropod dinosaurs likely interacted in a variety of ways.

How do modern predators interact?

Lions live in male groups of 4 to 40 lions, but females are the primary predators.

Komodo dragons are mostly solitary, gathering only to reproduce and feed. However, the dominant males eat first.

Tasmanian devils typically live and hunt alone. However, they often gather in packs to feed and share their prey.

Wolves live and hunt in family packs, which consist of a pair of breeding wolves, non-breeding adult wolves, and cubs.

Crocodiles are typically solitary, although newly hatched crocodiles often huddle together, and some species will continue to live in family groups. Food leads to large gatherings, and some species will cooperate in hunting.

Evidence of group living

The Deinonychus fossils in Montana offer some evidence for group hunting, as all the dinosaurs apparently died at the same time. However, their deaths could also be due to a recent fight during a hunt, rather than cooperative hunting.

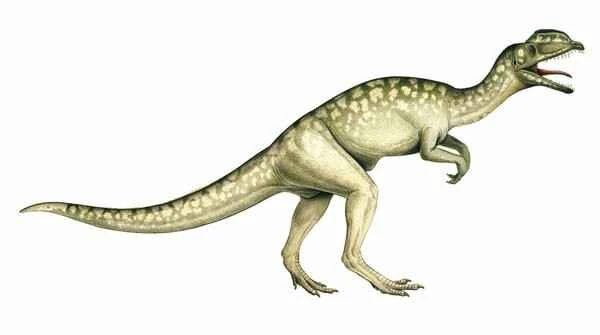

Jiangji Monolophosaurus was a uniquely shaped theropod dinosaur that lived in Asia approximately 170 million years ago. Its skull crest may have served as a display to attract mates or amplify its calls.

Giganotosaurus belongs to the same group as Allosaurus , and each hand has three fingers, a typical characteristic of Allosaurus. When Tyrannosaurus Rex was discovered in 1995 , it replaced Tyrannosaurus Rex as the largest carnivorous dinosaur. Giganotosaurus may have lived in a family, as at least four different ages of dinosaurs have been found in fossil bedrock in Argentina.

The Cryospora had eyes, facial ridges, and a crest on its horns. They were relatively fragile, so this feature was likely used for courtship displays. Cryospora were discovered in Antarctica. Although Antarctica is relatively warm, its winter nights are long and still cool.

Dilophosaurus had two prominent crests on its head, possibly used for courtship displays or to help identify other members of the same species. The discovery of three individuals in the fossilized bone bed suggests that Dilophosaurus lived in small groups. As a medium-sized theropod dinosaur, hunting in packs allowed it to capture larger prey.